First World War

Population Explosion

Barrow during the First World War saw the highest ever number of people living here. Thousands of women were recruited to help in the shipyard. Eventually the Barrow works produced 6.8m shells and 8.7 million forgings and partly completed shells. But women also became tram drivers and teachers to name just a few of the occupations that benefitted from this vital female assistance.

Eighteen year old Alice Wycherley came from Manchester to work in the shipyard:

"In Vickers, it was at times like some medieval vision of hell, with the dull lights bestowing a blue cast over the blue skin. But worse, much worse, was the continual shortage of money. I had a good enough job on the gauge bench but it was not bringing in enough to keep me. By going on in alternative shifts I was able to pick up £1.12s.6d. which was certainly better. However, the hours seemed longer. Night shift lasted from 5pm until 7.30 the next morning."

The Funk Hole

There was no mass exodus from Barrow of men for the front line as the vast majority of Vickers’ employees were exempted from military service. Instead, shipyard workers were contributing to the war effort by building many submarines.

The shipyard was nicknamed the "Funk Hole” due to exemptions for its workers. Recruitment rallies were banned in the town to protect workers vital for the war effort. All this was reasonable and wouldn’t be questioned during the Second World War. But total war was new for Britain, where every aspect of life had to be trammelled into helping Britain win the war.

Badges (see BAWFM.04795.1) were issued to workers up and down the country. They were meant to protect men from accusations that they should be serving in the trenches instead of staying at home. Members of the Order of the White Feather handed out these symbols of cowardice to men in civilian clothing to try to boost recruitment to the army.

Weary March to Victory

By the beginning of 1917 men and women were tired: of the appalling numbers dying in the "Great War”, of working very long hours and of no end in sight.

German U-boat action was successful in sinking ships destined for Britain to supply food. Shortages in potatoes, sugar, beer and butter became matters of public concern. Sugar and fish prices had doubled until Government controls brought some stability after 1917.

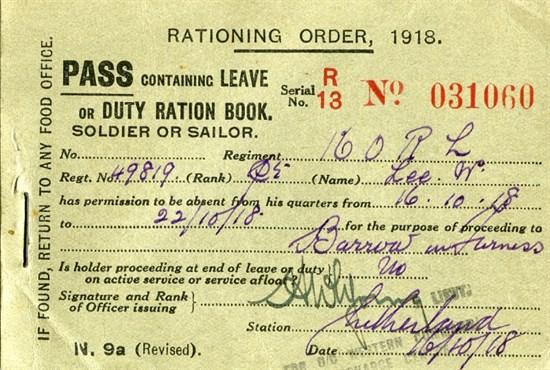

Coal, the mainstay of heat, power and light in Britain had jumped up in price and rents were also significantly higher. Families kept their heads above water through overtime. The government finally reacted to public pressure and introduced limited rationing in 1917 (ration book for a soldier or sailor pictured). More allotments than ever were pressed into use and farmers successfully increased food production.

There was relief and joy at the declaration of the end of fighting in November 1918. However with 750,000 British war dead most families would have lost a cousin, uncle, in-law, father or son. It would have been impossible to forget those victims of the war.

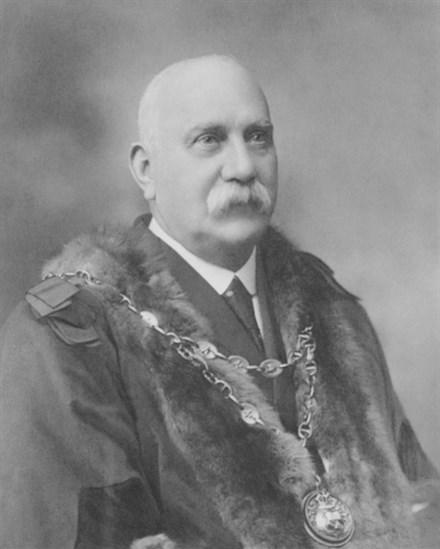

"We have smashed the Hun" (Alfred Barrow, Barrow's Mayor)

Barrow put on an impromptu afternoon holiday once Armistice was declared on 11th November 1918. However, the prevalent mood in the town was not one of unbridled rejoicing. There were parades and fireworks and accounts of soldiers and sailors "being much in favour with enthusiastic munition girls”, but there was also an acknowledgement that the years of hardship and loss demanded a measure of restraint and dignity. The mood was best summed up by an editorial in the first issue of the Municipal School magazine:

"We could not forget that at our elbow were many who had passed through the furnace of sorrow and trial during these memorable years.”