Iron and Steelworks

Legacy

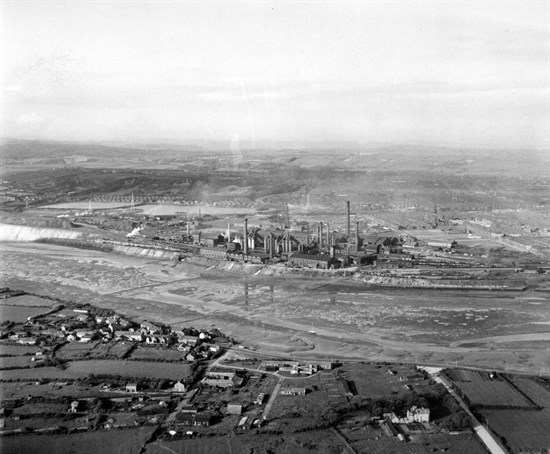

Today the size and success of Barrow's Iron and Steelworks have almost been forgotten. There is virtually no physical trace of the works in Barrow and sadly no great archive or collection of objects were donated to the Dock Museum. The most prominent reminder of the might of the works arethe slag banks, piles of industrial waste from the Iron and Steelworks, which have slowly been reclaimed by nature and are now a pleasant walk with great views over Barrow and Walney.

However, the story of the iron and steel works is an important one in Barrow's history the company drove growth in Victorian Barrow. Without the iron and steel works the shipyard probably wouldn't have been set up.

Early Days

Iron ore had been mined in Furness for centuries but on a commercial scale only from about the 1770s. The opening of the Furness Railway and the discovery of a massive deposit of iron ore at Park were vital in transforming Barrow.

Furness iron ore was of a type called haematite, given that name because of its blood red colour (see left). It contained a high iron content and was free of phosphoric impurities. This type of high-grade ore would give Barrow a helpful advantage when the iron and steel works were established in the 1850s and 1860s.

But it was the shelter of Walney island, offering a safe harbour at Barrow, that was the most obvious advantage in the 18th century. From about the 1740s a small port developed to carry away Furness iron ore to smelting works in Wales and the Midlands. Four jetties were built out into the Channel to ease the loading of ore boats, the first in 1790, the last in 1842.

By 1854 some 360,000 tons of iron ore were being raised in Furness, almost all of which was shipped out through the port of Barrow. Three years earlier Henry Schneider, after years of relative failure, had opened a massive iron deposit at Park near Askam. It was not much of a step in imagination to consider using Furness ore in a local ironworks – one small step for man, a giant leap for Barrow.

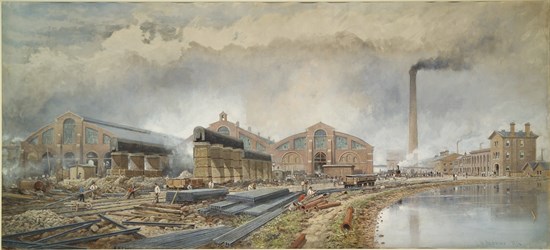

Henry Schneider and Robert Hannay put their new ironworks into blast in 1859. Two years later the railway line from Barnard Castle to Tebay filled in a missing gap in the railway network. This had been sponsored by the Furness Railway and Schneider and Hannay. At first it was thought of as a means of securing markets for Furness ore, but when it was opened it was used to bring in Durham coking coal to the Hindpool furnaces.

A Bessemer steel plant was started in Barrow in 1865 and the following year it merged with Schneider and Hannay’s ironworks to form the Barrow Haematite Steel Company. This company was the engine which was to drive Barrow’s growth for the next thirty years.

Legacy

Today the size and success of Barrow's Iron and Steelworks have almost been forgotten. There is virtually no physical trace of the works in Barrow and sadly no great archive or collection of objects were donated to the Dock Museum. The most prominent reminder of the might of the works arethe slag banks, piles of industrial waste from the Iron and Steelworks, which have slowly been reclaimed by nature and are now a pleasant walk with great views over Barrow and Walney.

However, the story of the iron and steel works is an important one in Barrow's history the company drove growth in Victorian Barrow. Without the iron and steel works the shipyard probably wouldn't have been set up.

Decline

The decline of the Steel Company was a slow one with production finally ending in 1984.

Barrow Haematite Steel Company faced increasing competition from British and foreign steelworks and the slowing down of railway building reduced potential markets. A Hindpool workforce of 3,500 in 1900 was reduced to 1,500 by 1911. Furness iron ore production declined; Stank mines were closed in 1901 and Lindal Moor mines shut down for a time in 1904. Things became worse after the end of the First World War: there was a collapse of the markets for iron and steel products in the worldwide depression.

After decades of uncertainty, threats of closure and mini-revivals, Barrow’s iron and steel industry, on which the town had been founded, came to an end. The ironworks closed in 1963 with the loss of over 700 jobs; the steelworks finally stopped production in 1984. Although both had long ceased to be main players in the town’s economy, their passing was a huge symbolic blow, especially as they had not been replaced despite a spate of post-war initiatives.

Today a sculpture in Barrow's town centre shows the steel making process and the worldwide export of Barrovian steel. This is the one large-scale reminder of what had been the engine for Barrow's very rapid growth in the nineteenth century.